In the Silence of Gir, a Village Called Aramness

By Prabhjot Bedi, Editor, Hospemag.

This feature is part of Experiences That Stay With You, an editor-led exploration of places remembered not for their amenities, but for how they made us feel.

An Indian lodge built not for scale, but for soul, crafted by land, people and patience.

In the late afternoon light at Aramness, I find Jimmy Patel, owner and creator of this wild little universe, not in an office or behind a desk, but stretched out on the cushioned bench of the poolside, coffee‑shop‑esque space. He looks like a guest between game drives. Not the person who bet time, money and reputation on an Indian wildlife lodge that begins at a thousand dollars a night.

He gets up immediately, warmth radiating. I sit where he was sprawled out, almost imitating the lions he loves to photograph. This is his favourite spot, he tells me. It is where he feels complete.

That word, complete, sits at the centre of Aramness.

A Piece of Land That Refused To Be Ordinary

Long before there were kothis, a haveli, or a signature welcome, there was meadowed land with four teak trees and a couple of acacias, surrounded by forest. No roads cutting through. No passing traffic. No city noise leaking in. In modern India, that kind of silence is almost a rumour.

Jimmy’s earliest memory of this place is not numbers on a feasibility report but the sound of nothing. “It didn’t feel connected to the outside world,” he recalls. “You just felt… cut off, in the best possible way.” From that first visit, he knew two things. One, he had to build something here. Two, whatever he built could not feel new. The lodge would have to look as if the forest had been leaning on it for decades.

Construction mirrored his approach to people. It began conventionally then changed when a better way emerged for the land and the community. Around 150–200 people worked on site at peak construction. Many came from the neighbouring villages. Some still live here today, as gardeners, pool attendants, butlers and supervisors. The lodge and the staff village grew together.

During COVID, as India watched workers walk home, Jimmy made the opposite call. Instead of shutting the site, he and his family moved in for 78 days to house and feed all 120 labourers, sharing the same land and the same garden.

To understand Aramness, start there: people were never treated like a line item on a cost sheet.

Building a Village, Not a Hotel

“Ness” means village. The lodge is laid out as a village would be: haveli at the heart, kothisspread like homes, a vegetable garden feeding both guests and staff, and a staff village that echoes the same rooflines and mud tiles as the guest accommodation.

From the beginning, Aramness was meant to be boutique, intimate and stubbornly personal. “We can’t do a 30‑key Aramness in a city,” he says, almost amused at the thought. “The service we want just doesn’t survive those numbers.”

Future lodges in Bandhavgarh and Pench will be smaller than Aramness, Gir, not larger.

Ask why he prioritises an independent brand over a global flag and he does not reply with positioning jargon. He talks about smell, colour and memory.

“Every brand has its own DNA,” he says. “You walk into a Four Seasons, Taj or Oberoi and within minutes you know where you are. The fragrance, the way you are greeted, the colours, the rituals. I wanted that clarity for us. If someone closes their eyes and thinks of Aramness, something specific should come back.”

To get there, he did something most owners never have the patience for. Before a single brick was laid, he and the design‑consulting team at Fox Browne Creative spent nine months writing a ‘Day in the Life of an Aramness Guest’ document.

Every moment, from pick up at the airport, to the first chai, to how a guest might sit by the pool at 3 p.m., was imagined, written, debated, walked through physically, and then refined. They asked of every space: If someone sits here, what do they see, need or feel? That obsessive empathy became the north star.

The Owner Who Refuses To Be a Hotelier

JIMMY patel

Jimmy is wary of labels. “I still don’t call myself a hotelier,” he laughs. “When we started, it was my first day. I’ve been learning ever since.”

That humility is disarming. He listened, deeply, to his design and operations partners. When HVS ran feasibility, the prudent path was obvious: attach a known luxury flag, ease distribution, lower perceived risk.

He declined.

“We were told starting at a thousand dollars without a brand was crazy,” he says. “But once we knew what we were building, the rate was not just about money. It was a signal. To ourselves, to guests, to the team. If you promise a certain level of service and experience, you can’t price it like something else and then cut corners to make it work.”

To this day, he refuses to manage Aramness through fear of monthly P&Ls. “We know our numbers,” he clarifies, “but we don’t live under them. The moment you over‑focus on cost, the instinct is to stop things. Stop this training. Stop this staff event. Stop that ingredient. I would rather keep adding value than spend my life cutting.”

The General Manager Who Prefers Villages to Cities

Parikshit

If Jimmy dreamt Aramness into existence, Parikshit, the General Manager, lives that dream day after day.

He began as a chef but left city kitchens because he wanted no part of four‑hour commutes and windowless basements. Took a trainee naturalist role he found online, moved to a remote tiger reserve he had never seen. Became a naturalist, then camp manager.

“I always wanted to be in a boutique setup where I know my guests and they know me,” he says. “Ten years later, if they think of India and remember a manager who took care of them, I’m happy.”

That preference for small scale drives decisions you can feel as a guest. You are not processed; you are received.

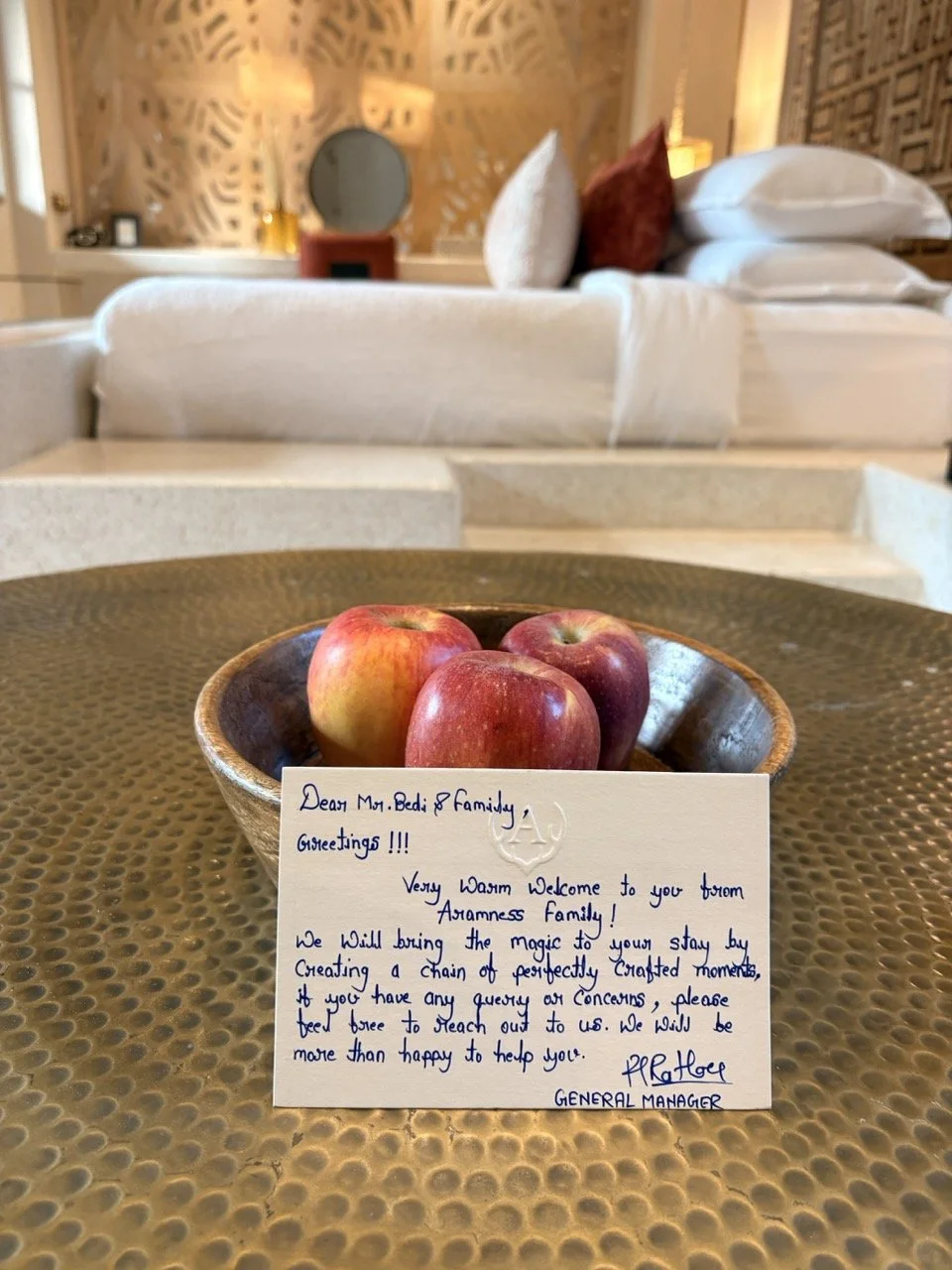

At arrival, the signature Aramness welcome unfolds. The entire village comes out – front office, housekeeping, gardeners, butlers, managers. There is music, drumming, and movement. On paper it sounds theatrical. In person it feels like something else entirely: a village coming to the gate, genuinely delighted that you have arrived.

Parikshit is clear about why it works. “You can’t just tell people to do this,” he says. “You have to do it yourself. If they see the owner, the lodge manager, everyone out there – smiling, clapping, welcoming – it stops being a task and becomes who we are.”

The welcome is followed by the team introduction and a safety briefing. It is not a scripted monologue. It is a moment of recognition.

He introduces individuals, not departments.

“This is Arun, your housekeeper who will look after your kothi. This is Hussain, the gardener who keeps the paths the way you see them. This is Vikas from the kitchen – do tell him if you want something special.”

It sounds simple. It does something many hotels miss: it puts names and faces to invisible labour. Staff feel seen. Guests understand that the people who will care for them are not interchangeable uniforms.

Recruitment follows the same practicality. They look for stability and a love for nature.

“It’s a small village,” he says. “If you don’t enjoy the place, the remoteness, the nature, no amount of training can fix it. But if you do, you’ll thrive.”

The Staff Village That Actually Deserves the Name

Back‑of‑house accommodation is one of the great hypocrisies of hospitality. Guest‑facing brands talk about warmth, family and culture while housing their teams in cramped, windowless blocks.

At Aramness, the staff village is not a metaphor. It looks and feels like what the guest side promises.

Mud‑tiled roofs nod to the guest kothis. A volleyball court where matches are serious and conspiratorial. Chess and carrom games that run late. People cooking together in the cafeteria kitchen.

On Diwali, the team organised staff lunch, sweets, rangoli and diyas laid out in front of each staff‑room door, a small private festival for people who spend the official one serving guests.

Attrition, predictably, is roughly half of comparable properties.

Food as a Love Language

Jimmy calls food a love language, an extension of the way Indian families express care. “At home, our mothers show love through parathas,” he says. “Here, we just extended that idea. It’s not about twenty dishes on a buffet. Even if you serve one thing, if it is cooked authentically, with attention, it says: we care.”

Chef Vikas Das feels that same responsibility.

Chef Vikas Das

He reads guests early. “At the team introduction, the way the guest interacts is the best way to understand how the guests will behave in the next two days,” he says, half‑joking, completely serious. There are guests who immediately engage, ask questions, and want to know where vegetables come from. There are guests who say nothing and never complain – but never return. Those worry him more.

After the first meal, he adjusts the menu around them. More Gujarati depth here. Less spice there. A smaller dessert portion for the guest who clearly wants seconds but is being polite.

Children are the centre of gravity.

“Make the child happy, the whole family is happy.”

So he lets them into the pizza corner. Small aprons. Caps. Dough in their hands. He shows them how to stretch it and place toppings. In the photograph that goes home and onto phones and walls, the child is in the foreground. He is happy being a blur in the background.

The vegetable garden is not a sustainability slide for presentations. It is part of the daily conversation with guests. Instead of pre‑prepping generic gravies, the kitchen looks at what is fresh and asks, “We have this today – shall we cook it for you?” Guests say yes more often than not.

Now and then, the system flips entirely. An Australian guest, originally from Bihar, mentioned missing home food. The chef and a colleague rolled up their sleeves and prepared litti chokha – rustic, smoky, unapologetically local. For a thousand‑dollar‑a‑night lodge to serve litti chokha is not a gimmick. It says your cravings matter.

The team absorbs another lesson from owners and trainers like Lesley: everyone at the table is a guest. One evening, Chef Das took orders from a group and walked off—then stopped, turned back, and asked lodge naturalist Kamaxi what she wanted to eat. “She’s a colleague,” he says, “but in that moment, she’s also a guest at that table. If the guests are cared for and the team isn’t, something’s off.”

Small corrections. Culture‑defining.

The Butler Who Was Once Afraid of Lions

SHIV

Luxury hospitality has long wrestled with a quiet contradiction: how to offer attentive service without turning staff into performers of servility.

Shiv was our butler, the bridge between us and the lodge. He came from business hotels where air-conditioning mattered more than silence, and followed a friend’s trip all the way to a jungle lodge near Junagadh—train, bus, then a car disappearing into the forest. The first months scared him; knowing lions lived here is one thing, cycling home in the dark is another. It took a few months for the fear to fade. Now, the jungle is home.

Every guest gets butler service, but it’s not scripted. Shiv translates passing comments into care: a mention of being tired becomes dinner in the kothi; a request for seconds becomes an extra portion the next day. He’s in the business of conjuring ease.

He also had to rethink hierarchy. In his old jobs, owners were distant. Here, they wander into the kitchen, taste dishes, joke with the dishwasher as easily as with the GM. “They don’t behave like ‘sir’ and ‘madam’ at all,” he says. “It’s different.”

The difference shows up in staff experiences. He experienced wellness as a guest would, joining yoga, a detox routine, and sound healing. He sees me come back from a session and smiles “It’s difficult to stay awake in the sound healing, isn’t it!”

This isn’t servility nor a performance.

Wellness Without Buzzwords

DR JABBAR

In a market high on wellness buzzwords – IV drips, biohacking, detox packages – Aramnessstays quietly Indian and grounded.

Dr Jabbar left a corporate spa track for the forest. He anchors wellness around movement, breath and energy, eschewing quick‑fix fads for something rooted in place. He first visited with no plan to change jobs. He just wanted to see the property and a part of Gujarat he didn’t know.

As the car left the highway and moved deeper through dry forest, he saw herons, deer and, on that first drive, a lioness. By the time he reached the gate, there was already a sense of something in the land. At the entrance, he was welcomed with dhols, treated not as a candidate but as a guest.

His onboarding mirrored that philosophy. No HR marathon. No induction deck. Instead, a walk through the lodge, the staff village, the cafeteria, the treatment spaces. A safari. Chai at a village stop. See the forest the way guests would.

Wellness here is less about the menu card and more about what the land is already doing.

“Safaris are wellness,” he says. “You go into clean air. You see animals, trees, and light. You disconnect from your usual life. It is a detox.”

The decision to not put televisions in rooms follows the same logic. The pretty kothis have more outdoor space than indoor. Verandas and upstairs terraces invite people out. Most guests naturally cut back on phone use. They talk, read, do nothing, or listen to the forest.

In summer and monsoon, when afternoon safaris are less comfortable, the plan is clear: push wellness. Early morning drives, then long, unhurried days of treatments, yoga and rest.

The idea is not to add activity. It is to design for slowness that city life has pushed to the margins.

The Naturalists: Translating the Forest

KAMAXI

Wildlife lodges rise or fall on a quiet asset: their naturalists. At Aramness, they’re storytellers, safety nets, and sometimes the conscience of the place.

Kamaxi arrived after a stint at Oberoi Vanyavilas, where her first day meant aarti, tikka and a performance: she sang. At Aramness, her welcome was different: long walks, lessons in hospitality, a directness that felt less ceremonial and more demanding. No big brand to hide behind.

On a week of heavy rain, she lent property ponchos to guests who weren’t prepared. Within minutes, the ponchos failed. The guests were wet and understandably annoyed. She carried that feedback back to the lodge manager and asked for better gear. It was procured.

On the way back from the safari, she asks us what we would like. “Your favourite Aramness tea or shall we try something new this evening?”. She texts the lodge team when we are about ten minutes away. The brew is ready when we arrive.

How did you learn this? I ask. “It’s the way we all do it,” she says.

When she speaks of the forest: flora, fauna, the whole breathing world, it sounds as if the land has chosen its voice. Naturalists stand where guest experience meets truth, seeing first whether a lodge’s talk about respect extends beyond the brochure.

At Aramness, she feels it does.

The Trainer Who Builds a House, Not a Hotel

lesley fox

Across conversations with Aramness team members, one name recurs with particular warmth: Lesley Fox. Fox Browne Creative’s training lead and culture shaper.

Lesley’s South African roots shaped a belief in dignity, access and empowerment. She speaks openly about coming from a country with a painful, unequal past, and carries a Mandela‑inspired conviction that leadership is about creating conditions for others to shine. In training rooms, that shows up as charitable assumption, dance and movement that cross language barriers, and a deep patience for making sure every person truly understands the details.

“Adults learn by doing, not by listening.”

She is in her sixties, energetic enough to shame teams half her age. She will pick up a broom, clear cobwebs, drag furniture, then run a training session that ends with half the staff dancing.

“I went back to Botswana last week and met the staff we trained two or three years ago. They came, badaboom, badaboom, dancing as they approached. I didn’t have to say a word.” I can see her eyes twinkle as she tells me this.

Her standards are meticulous. She notices if something is on the wrong side of a bed, if a bottle label turns away from the guest, if a prop in the library has shifted from the original styling photographs. She uses those observations not to scold but to teach: this is why this object is here; this is the story it carries.

Her TV and film background makes that rigour natural: tight deadlines, clear briefs and contingency planning. As she puts it, it taught her to go down the rabbit hole with alternatives and the Jerry Maguire line, “help me help you,” turning training into disciplined production where the story is protected under pressure.

Hiring and development follow a simple lens: place people where they will thrive.

It is tempting to describe Aramness as India’s answer to African safari luxury. On some level, it is. But to leave it at that would be lazy. Aramness is not an imitation of Africa with Indian props. It is fundamentally Indian, rooted in Gujarati land, staffed substantially by local people, driven by an owner who cares more about authenticity than Instagram. The idea, Jimmy says, is not to replicate Africa. It is to give guests an Indian wildlife circuit that feels as considered, as safe and as emotionally resonant as any international itinerary.

And do it with the parks’ carrying capacity in mind. With Supreme Court limits on vehicle numbers inside reserves, building giant 100‑room lodges makes no sense. You cannot deliver intimate wildlife experiences to that many people in one place without overwhelming the park.

Aramness’ answer is to stay small and focus on depth rather than scale. Not mainstream. But it respects both guest experience and ecology.

There is a reason this story has spent so many words on people and so few on thread counts.

Luxury, in the old language of hospitality, is often reduced to objects. Aramness has those credentials. Kothis with brass fittings, retro fans, a hand-carved marble basin with a lion gargoyle, even a marble bathtub with movie-star energy. Kutchi lippan walls catch the light; an upholstered jhoola hangs from antique brass chains; vintage textiles, a bar made from old printing blocks. It’s a space built from craft, memory, and intent.

But what stays with you long after you leave is not the stone. It is the people.

It is Jimmy, stretched out by the pool, talking about patience and ethos rather than GOP.

It is Parikshit, first to arrive and last to leave.

It is Chef Das, reading a family’s mood from a single “namaste”.

It is Shiv, the butler, a calm presence for guests.

It is Dr Jabbar, who measures success in the stories guests tell.

It is Kamaxi, the naturalist who makes you a lifer.

And it is dozens of people whose names you may not remember but whose work you feel.

You can build a beautiful lodge with money. You can only build a village with people.

Before we part, I ask Jimmy what he’d improve. He goes quiet, the kind of quiet that comes from having lived inside every brick and decision for years. I brace for a list. He simply looks around, smiles, and says, “Nothing.”

I find myself agreeing with him.

You can experience pure rejuvenation with Aramness' newly unveiled Wellness Immersion.Reach out to reservation@aramness.com to reserve your transformative escape today.

Instagram: @aramness

This story is part of Experiences That Stay With You, Hospemag’s ongoing editorial series exploring the people, places, and moments that linger long after the experience ends. Each feature is shaped through first-hand encounters and chosen for what it leaves behind.

If you believe your work, your property, or your story belongs here, and is best experienced in person, you’re welcome to write to us at editor@hospemag.me